A songstress and her memories of World War II

“One day, the grown-ups were playing mahjong and they asked me to make some tea for them. So off I went, holding a kettle in my arms, when I passed by the waste burning area located by the gate, that military truck was just parked right next to the council office… I heard them jump off the vehicle one by one, so I took a quick glance but decided to just keep walking. That was close! The Japanese did not see me there. I managed to make some tea, but upon my return, they told me that the Japanese were here!”

Lee Yit Ming with her precious song books. (photo by Mango Loke)

Lee Yit Ming was talkative. She was sitting on her bed, as she rattled off the memories of her encounter with the Japanese troops during World War II. Being a bright and chirpy girl, she had a happy childhood and teenage years, in spite of the difficult disease and her struggles through the miserable days of famine in the settlement during the war.

This inmate, now 86 years of age, is from Batu Caves, Selayang. When she was 6, her family sent her to the Sungai Buloh Settlement due to her deteriorating condition. Lee Yit Ming remembered the time when she had just contracted leprosy, her grandfather took her to a temple one day and they stayed there for the night to pray for blessings. That evening, she and her grandfather spent a soothing night sleeping in a cot, as the breeze sent shadows of the trees dancing on the ground in the moonlit courtyard.

Yit Ming’s father had a fish-farming pond built right by their home, located far away from the other residences, so no one around the area was aware of her infection. On the day she reported to the leprosarium, she departed at 4 o’clock in the morning, in pitch dark, so that no one would notice. Her father took her all the way from Batu Caves to Sungai Buloh on a bicycle. As they were riding through the woods in Sungai Buloh, they heard a faint roar of a tiger.

“My dad was terrified, so he turned on the headlight on his bicycle. If the tiger had come out and attacked us, that would have been the end!” Lee Yit Ming lost her eyesight two years ago, but her mind remained so sharp that her memories of the past were as vivid as though it had only happened yesterday.

After reporting to the settlement, the authorities assigned Lee Yit Ming to a chalet where she stayed with a middle-aged, female inmate. She said that there was no Children’s Ward at that time and each child was arranged to stay with an adult in the chalets. Her father would visit her every once in a while, however it was always done secretly, because, “He did not want people to know about it,” said Lee Yit Ming.

She was a treasure to her grandmother, who would visit her often. Every time before they parted at the gate, her grandmother would say to her, sobbing, “Goodbye, Ah Yit, grandma has got to go now…” Yit Ming cried too when she saw tears rolling down her grandmother’s face.

“My grandpa has no sisters, neither does my dad. There were all boys in my family, no girls. They wanted a girl very badly. I was the first daughter born to the family and they were thrilled!” she said. “But the bliss lasted only for three years or so, before I suffered a flare up. My grandma cried her heart out when that happened!”

Her grandfather passed away all of a sudden, when she was 8 years old. She then applied for two weeks of compassionate leave from Mr Fisher, the Inmate Lay Superintendent, but only returned to the settlement two years later.

Lee would use her wheel chair to transport her utensils for washing. (photo by Mango Loke)

“It was hard to part again with my family!” she said. At that time, however, her condition has worsened, making her ears a reddish hue, so her father had no choice but to send her back to the Sungai Buloh Settlement.

Soon after she returned to the settlement, the war broke out. It took place so close to the leprosarium that the 11-year-old Lee Yit Ming had witnessed warplanes dropping bombs from the sky with her own eyes. “When they bombarded Batu Arang, I saw the bombs falling all the way down, and the blast shook the whole place up.”

In 1941, the Japanese occupation began after the British troops withdrew from Malaya, a rule that lasted for three years and eight months. Although the Japanese did not take over the leprosarium and the management team remained unchanged, Malaya suffered a severe food crisis at that time and the settlement was no exception.

“It was really horrible. There was nothing to eat. It was not too bad at the beginning because we still had some things to eat… But soon, there was nothing much left. Then, we only had about 100 grams of rice, which is not even enough for a congee,” she said.

According to Lee Yit Ming, everyone used to receive about 450 grams of rice a day, but the rice ration dwindled to 100 grams per person per day after the war broke out. There was a severe shortage of firewood, rice, cooking oil and salt, so severe that the authority stopped distributing rations. In the end, the inmates had no choice but to feed on tapiocas dug from the ground, and blanched sweet potato leaves. As a result, all of the children then were bony, sallow-skinned and pot-bellied.

During the famine, the inmates tried all possible ways to fill their tummies. The entire community – men, women, children and the elderly – worked together to produce noodles from tapioca flour. The tapiocas were peeled, sliced and soaked in water overnight, before being sun-dried and pounded into tapioca flour with a foot-powered pounder. The inmates gave the noodles a name, called the “Tokyo Sticky Rice.” Even to this day, Lee Yit Ming has not forgotten how great the “Tokyo Stick Rice” tasted.

When she was a lively 12-year-old, she used to tag along when the male inmates went lumbering in the woods. The men worked in pairs to bring trees down with saws. When the trees fell, she would haul them back to the settlement and wait for the men to chop them into firewood. Each pile of firewood was sold for 4 dollars. Using the earnings, she would buy something to munch on.

At that time, the inmates had not much else to do, so visiting other inmates was a regular affair. When a few of the male inmates dropped by, they taught Yit Ming classical Chinese poems and composed verses in Hakka. Lee Yit Ming was so talented that she could memorise everything they taught her effortlessly.

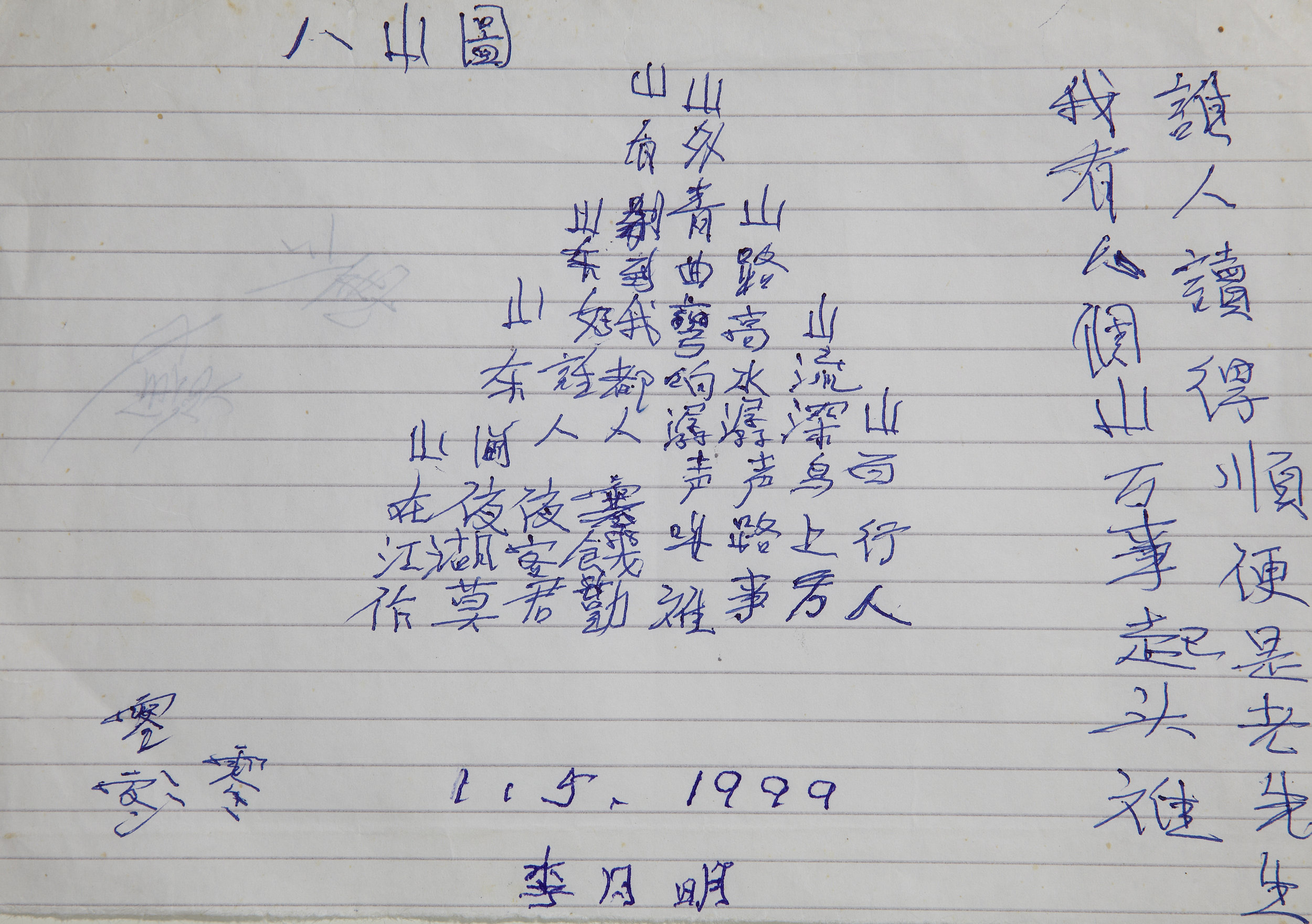

During the interview, she fluently recited a “mountain-shaped poem”, entitled Eight Mountains, in the Hakka dialect:

Lee’s hand written poem of the “Eight Mountains”.(photo by Mango Loke)

“I have eight mountains; Starting up is always challenging.

Whoever reads fluently, He is a savvy.

A road winding through the valleys,

The murmur of streams flowing down from the high mountains.

Birds singing deep in the ravines,

Thousands of arduous miles for travellers to journey.

My advice for you is not to be a far-journeyer,

For you may starve through freezing nights between the ridges.

The mountain in the east is, by all accounts, a great distance to cover,

But I say there is more.”

The verse was written by Song Xiang, an exceptional literary talent born in the reign of Qianlong Emperor of Qing Dynasty, but the version that came down to the Valley of Hope was slightly different from the original.

She formed the shape of a mountain with her fingertips and said, “When you read this Eight Mountains verse, you cannot just read it all the way like that. You need to do it in a zigzag pattern. Since this is a mountainous road, you must follow its twists and turns as you read.”

She then reeled off another Hakka verse (that has a square outline) and a Cantonese poem (that is shaped like a cross) off the top of her head. Her memory is amazingly sharp for her age.

“I love and enjoy these very much. They are my treasure!” she said.

Lee Yit Ming stopped going to school after the war broke out. The school, closed and overgrown with weeds because of the war, only resumed classes after the Japanese surrendered. By then, Lee Yit Ming was already a 16-year-old lady.

She said that there were only about 18 children (and teenagers) at that time. When World War II ended, they were all relocated to the Children’s Ward, instead of resuming their stay with elder female inmates.

Then, lessons at the Travers School were taught in English. She remembered having mathematics, hygiene and geography classes at school, and learning her own mother tongue in the afternoon. Hence, she can speak simple English and Mandarin.

Lee Yit Ming, a quick-learner with a good memory, had always been a high achiever at school. She proudly said, “I was always ranked above third place in examinations, always No.1 or No.2, if not tied with somebody else (for the first or second place).” Regrettably, she dropped out of school when she was in Primary 4.

When she grew up, the nurses wanted patients cleared of leprosy bacilli to be discharged because the settlement was full. She was requested by the nurses to leave the settlement and return home, but she had long been out of touch with her family. So, when the authority proposed to transfer her to a nursing home in Serdang, she had no choice but to accept.

“I was put in an old folk’s home when I was 20,” she chuckled. “I spent 11 years there.”

After moving to the nursing home, Lee Yit Ming sewed uniforms for the inmates in exchange for room and board. Soon, some of the elderly and the nurses came to her for tailoring and alteration work, and she managed to earn some income from it. Lee Yit Ming was then a playful and lively 20-year-old, and a fashionista who loved to make a variety of outfits for herself.

“I made a lot of clothes over the 11 years, designs based on what famous artists like Bai Longling and Lin Cui wore. I made them myself and tailored the clothes based on their photographs.”

One day, after sewing a pencil skirt for a customer, she thought she deserved one too. So, she went all the way to Kuala Lumpur to buy a piece of fabric to make another one for herself.

“Oh, here is my embroidered pillowcase. I made it myself. See? This is in violet,” she suddenly reached for her pillow. “Violet,” she said, this time in English. On her pillowcase, there was indeed a beautifully embroidered purple flowers. This half-century-old needlecraft is well kept to this day.

“A cousin sister of a nurse at the nursing home wanted some embroidery work for her younger brother who was getting married soon. My embroidery for the groom-to-be earned me 5 dollars. That used to be a huge amount, like 500 dollars today!”

During her stay in the nursing home, she tried to look for a job outside the settlement, only to end up in failure, and even an encounter with a con man. Since then, she settled with making money from her tailoring and embroidery work. At that time, the other inmates in the nursing home mocked her, but she just shrugged it off.

“When (the elderly) were happy, they would sing the Leper’s Song.” She laughed and sang in Cantonese, “Turns out there are holes in the soles, crazy worms keep digging… ” She paused and asked, “Do you understand the lyrics? It was sad to hear the song. It called us mad.”

“The Crazy Song goes like this, ‘Buy a canoe, get a boat…’ You know why?” she paused and asked. “Back then in Tong-san (China), if someone had a flare up because of leprosy, his family would put him in a small boat with a bit of food, send him off to sea and then let the boat sink on its own. They would not care when the boat will sink and when the poor fellow would die. That was how it used to be. That was what the old ladies sang.”

When asked of her feelings upon hearing these songs, she said, “So what? What else could I have done? I could not beat her up, could I? I heard it and I just picked up what they sang.”

One day, she yelled at an old man who peeked at her while she was in the shower. In defence, she tried to keep him away from her bed with a broomstick. However, she was expelled from the nursing home by the director because of this. So, she returned to the settlement and stayed with a nurse named, Sister Ah Hoi. Lee Yit Ming did the laundry and cleaned the floor for her. On top of that, she also took laundry orders from inmates and washed their clothes and bed linens.

Most of the articles of clothing she handled were uniforms, one set every two days for 7 dollars a month. She said it was a great deal of labour because she must starch and iron the uniforms after washing and drying them. She recollected an incident that happened during an English oral test she took at school – her teacher asked her what she would like to do upon graduation and she blurted out, “Dobi” (laundry worker). As much as it was just a word she uttered by accident, it somehow came true and she ended up washing clothes for others in real life.

When she was staying in a chalet, she used to grow ferns, but a downpour washed away all her efforts. So, she started working under the government employment, first as a cook and then as a ward attendant for eight years, with an allowance of RM136.08 per month.

Lonely is the mood and dim is the soul without singing. (photo by Mango Loke)

Twenty years ago, Lee Yit Ming had to move into the hospital ward due to her age. Her home shrank from a chalet to a hospital bed. Fortunately, poetry and music have been her greatest sustenance. She loved to take down lyrics in her youth and her favourite pastime was listening to music, singing and reciting poems. It was no surprise then that in the midst of our interview, she spontaneously hummed us the melody to You Are My Sunshine, an English song she learned as a child. Every note was perfectly in tune and her voice was beautiful. The next day, she called us for another video shooting session as an idea came to her: she would sing the Travers School’s anthem for us. Ever since the Travers School was closed down in the 1980s, its anthem was heard no more. A picture of Lee Yit Ming and her schoolmates jumping around on the lawn travelled in time and reappeared before us, as she sang the melodic school anthem once again.

She is 86 years old now and can only move around in a wheelchair because her legs have weakened. Still, she does her own dishes and laundry, and can even shower without anyone’s assistance.

Her loss of eyesight two years ago was a heavy blow for her. She had been living independently all the time and enjoyed singing and leafing through her collection of lyrics. Now, she feels as vulnerable as a candle in the wind, as if her life will wither any time. Fortunately, the hospital ward has been a heart-warming home for her, with an old wardmate, occupying a bed opposite her, always there to care for her each day, and a trusty radio by her bed.

Lee, who felt that her life was as vulnerable as “the candle in the wind”, drew her last breath in June 2017. (photo by Mango Loke)

Narrated by Lee Yit Ming

Interviewed by Chan Wei See & Wong San San

Written by Chan Wei See

Translated by Zoe Chan Yi En

Edited by Low Sue San